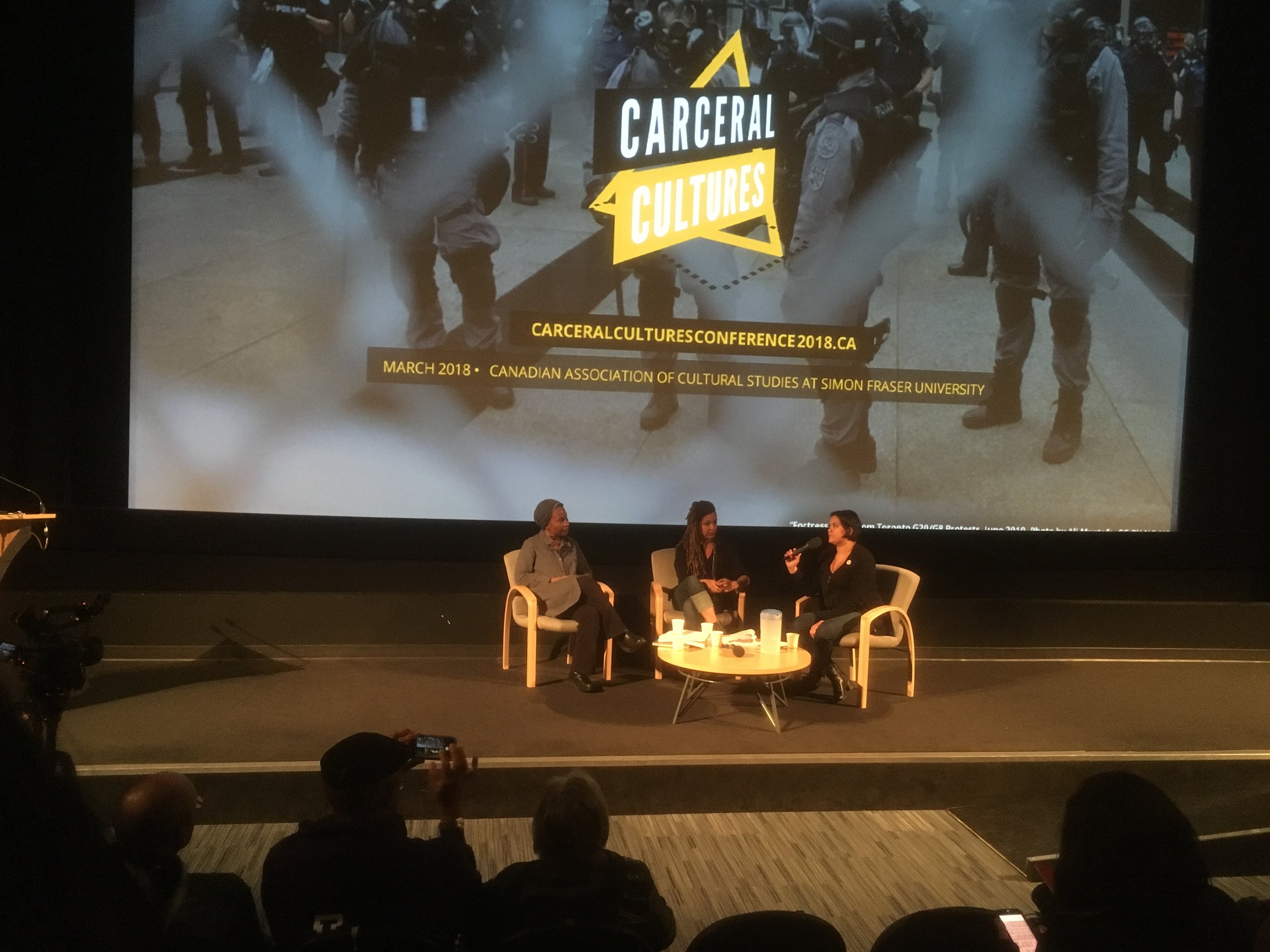

Joy James and Robyn Maynard in Conversation. Carceral Cultures Conference. Simon Fraser University. March 3, 2018

By Jeff Shantz

Joy James and Robyn Maynard have raised critical voices in calling out and confronting state violence, particularly in its multiple forms of policing and containment. They have provided potent and insightful analysis of, and tools for opposing, state-driven anti-Black racism in the United States and Canada. Their work offer important examples of scholarship as, and in solidarity with, activism. This conversation, hosted by the Carceral Cultures conference, was full of significant insights and relevant calls to action.

Joy James began her talk by telling those assembled that her thinking is somewhat muddled these days. And it is muddled by grief. Yet her analysis was clear and incisive. James reflects that anonymous people wake up and do the work of movements and resistance. It is motivated by love. And they often suffer anonymously. The criminalization and brutalization of care. The captive maternal.

The conversation, and James’ thinking about the captive maternal, is dedicated to Erica Garner who was killed by the systems of exploitation and oppression, as was her father Eric Garner, even if her death was less public, less dramatic. Her death can be attributed to the stresses of fighting for her dad, infamously murdered by New York police officer Daniel Panteleo who choked him to death on a Staten Island street. Over three years of fighting for justice took a toll on her. Erica Garner was constantly doing research on her dad’s case, and organizing demonstrations against the force that killed him, but not taking care of herself. Erica Garner found no justice from any of a supposedly progressive mayor, supposedly progressive governor, or Obama.

James suggested, in what is a significant reflection, that Erica Garner was rendered a non-entity in the movements because she was too unruly and her demands too “unreasonable.” Even social justice movements and activists can be too ready to make accommodations to power and authority, believing criminal justice systems can be reformed (even when based on brutality, erasure, and genocide) and careful not to threaten their own positionality (through “reform-minded” politics). Criminologists who accommodate cops in their departments can be like this. So the unruly are left to deal with it—to push for real change, to confront the institutions and agents of exploitation of oppression. And face the consequences.

James emphasized the illness and disease suffered by Black women who are fighting for justice. Incidents of stroke, heart disease, high blood pressure are not uncommon. She has studied this in different contexts including health issues among poor Black women organizing in Brazil, which she referenced in the talk.

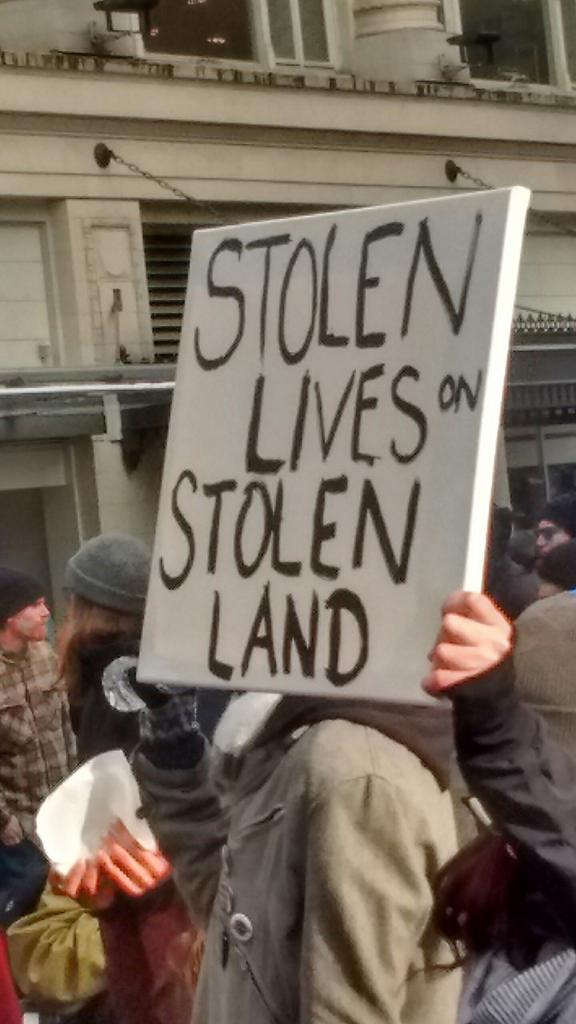

James noted that the origins of United States democracy are grounded in genocide and enslavement. The settler colonial state has had to deploy a captive maternal in its very development. Captive maternalism goes along with capitalist development. She referred to the distortions of those who view Thomas Jefferson as a “benevolent slave owner” and asked if he might also be posed as a “benevolent rapist” by those seeking to whitewash settler colonial violence at all costs. They have tried to erase Sally Hemmings from history, but the refusal by activists to forget her, and Jefferson’s violence against her, has led to her becoming an icon of resistance.

How does the captive maternal take back their generative powers?

Robyn Maynard offered a thoughtful and engaged response to James’ words. She began by asking what is considered a public tragedy. In part they are those that are fought over and remembered. Recalling words by Angela Davis she asked how caring for ourselves and our children can be recognized as revolutionary work. This is more than individual action.

Erica Garner was a victim of both state violence and state neglect. She suffered the isolation that family members of policing killings almost always face. Erica Garner’s death was private. It is seen as sad but no one is held accountable. We need to look at other institutions that failed Erica Garner—beyond the spectacular forms of state violence.

In this regard we must put a focus on the criminalization of Black motherhood and care giving, as ongoing histories. This includes but is by no means limited to welfare snitch lines and refugee women who are demonized and said to be “sending money to warlords” as has been said about Somali women. In abolitionism, not only do we need to eradicate prison. We need to eradicate child welfare systems that disproportionately capture Indigenous and Black children. And which expend vast social resources in doing so. Maynard points out that these child welfare systems spend more per child than most poor women even have.

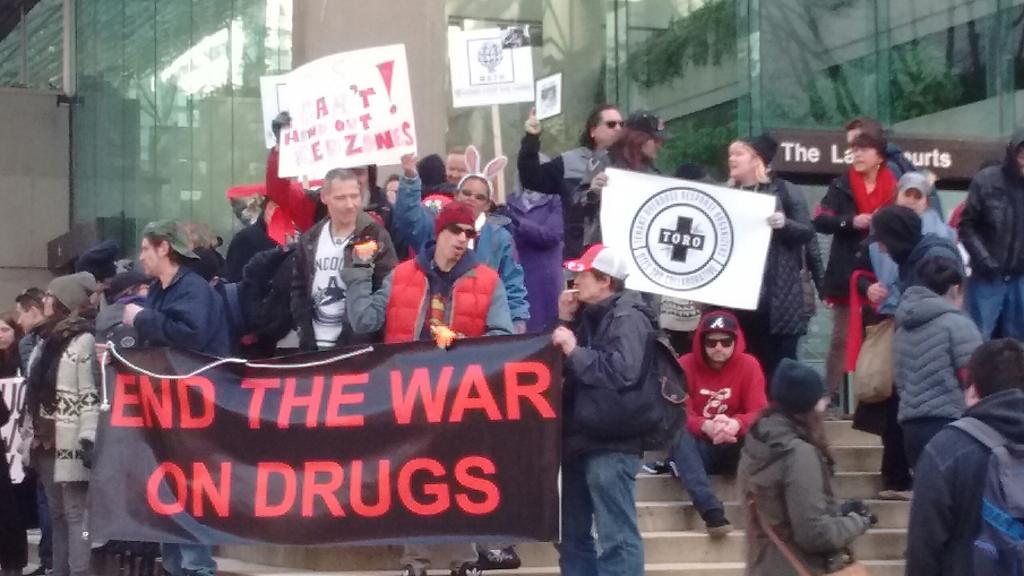

We need to address the fact of Indigenous women being killed disproportionately by drug policies. What happens to their families and communities?

For Maynard, as for James, we need to think about abolition in ways that are larger. We need to think about other sites of surveillance and punishment. And both speakers stressed that prisoners must be part of this, not only activists and academics—it must be relevant to prisoners.

One aspect of abolition that we need to start challenging now is in opposing police budgets. We need open campaigns to divest from police. This would address a range of interconnected issues of brutality, oppression, injustice, and social harm. From mass incarceration to drug overdoes deaths to violence against sex workers to ongoing colonial violence. We need to put resources instead toward other things that would bring real care and support to communities.

James pointed out that caregiving work, in families and socially, is done by women mostly. If women went on strike the system would fall apart. Straight up. This is the still relevant call of “Wages for Housework.” As James put it, we have to steal ourselves back from capital, from war, from misogyny.

To the credit of the speakers the conversation did not stay away from issues of ongoing imperialism and the role of the US and Canadian states. James reminded the audience that the US government has actively destabilized every national liberation movement around the globe for decades (while bringing in actual Nazis to develop their military and space programs). In her words the US is a war zone that exports war. Police in the US are often former soldiers who come back from Iraq and Afghanistan. They are trained to kill. And they shoot first, ask questions maybe never.

Maynard added that the control of migration and the theft of resources, in “home countries” and abroad are the ongoing legacies of slavery. Now it is posed as the restriction of movement and tightening border restrictions.

Robyn Maynard concluded her discussion by saying that she hopes that today’s resistance will address the real nature of the system, not only the boldfacedness of Trump who puts openly on loudspeaker what has often been the unspoken reality. Maynard is clear that it is not positive, or progressive, to seek a return to the “closeted” status quo of empire as maintained under Obama. James worries that under Trump people have gone from amusement to outrage to simply numb.

Poverty, racism, grief and depression all contributed to Erica Garner’s death. These are the structural manifestations of exploitation and oppression. Her father’s killer, officer Daniel Pantaleo has received promotions and pay increases. The only person ever arrested and charged in relation to Eric Garner’s murder was Ramsey Orta, the man who recorded the killing on cell phone video and took it from the realm of anonymity and police cover up that so many police killings of civilians are contained within.