By Jeff Shantz

A report on the second annual Metro Vancouver Aboriginal Executive Council conference. Vancouver Aboriginal Friendship Centre. February 13, 2018

The conference “Reversing the Psychology of Poverty: A Policy Engagement Conference” hosted by the Metro Vancouver Aboriginal Executive Council proved a lively, important, and compelling venue for discussing a range of crucial issues of truth, reconciliation, colonialism, anti-colonialism, decolonization, and justice (social, economic, political) in the present context. It went beyond its initial focus in some highly significant ways. Speakers included Kevin Barlow, Rocky James, Sue McIntyre, Chas Desjarlais, Dan Guinan, Ginger Gosnell-Myers, Colter Long, and Norm Leech.

The conference set out to analyse and critically develop approaches to the so-called psychology of poverty, a rightly contested notion that can have the consequence of individualizing social problems and locating them in personal rather than social factors. Several impacts of a psychology of poverty were identified. They included the following. First, living below the poverty line creates generations of people willing, even expecting to cope with less. That is they may stop asking for more, for what they deserve. Second, there is a learned defeatism that suggests things will never improve. Third, people can feel the need to take risks, opting for short term gain over longer term opportunities. Fourth, Indigenous people are pushed to internalize cultural identity as inferior. Fifth, anger and frustration (which can be productive or unproductive).

The issue of education is given much attention in discussions of reconciliation, and as a university instructor this is something of much concern. It is noted that education is healing but, at the same time, people have to heal before they can learn. These are integrated, but one cannot learn if some basic needs are not met (health, nutrition, housing, etc.).

Resistance and Resilience

Significantly the discussions very soon shifted focus organically to meaningful analyses of the structural and systemic roots of poverty and psychology. Several crucial issues were brought forward.

During the first question period it was posed that there is a need to shift focus away from the emphasis on trauma, that has characterized much reconciliation discourse, to the violence that causes trauma. Focusing on psychologies of trauma can serve to privilege the forces and structures of power.

The original violence that causes trauma is colonialism. Children are still put out into a colonial world, even if education and culture are done in the home, community, and schools. Emphasis is still on success in a colonized world. A key question is raised about reconciliation and restoration: “Is it building a world that is healthier or is it making people more individually “successful” (on certain markers of materiality) in a fundamentally unhealthy world?”

It is worth pointing out that services seem oriented toward changing the individual to make them appear less traumatized in a traumatized and traumatizing environment. But the environment remains largely unchanged and it remains harmful and destructive.

Resistance and renewal must be in balance in addressing structural colonial violence. Four emphases were brought forward. These were as follows. First, food security and nutrition. Second, affordability. Third, a sense of belonging. Fourth, a meaningful sense of hope for the future. And this is all to be done while not forgetting about the violence of colonialism and domination. In belonging one can feel contributing. In contributing one can feel hopeful and create the conditions for change that they want to see. This is forward thinking and positive rather than reacting in the world to seemingly outside conditions.

There is a need to create home, not only homes. Physical, emotional, nutritional needs must be addressed. Attention needs to be given to “spiritual homelessness” on stolen lands. Real questions are posed to us about how to maintain collectivism in an individualist and individualizing culture.

On Justice

The final session involved an explicit and sustained focus on justice and notions of social versus criminal justice. As a criminologist, and active member of the Social Justice Centre, I was especially attuned to this discussion and will focus most of my report here. The session was facilitated by Norm Leech with Colter Long.

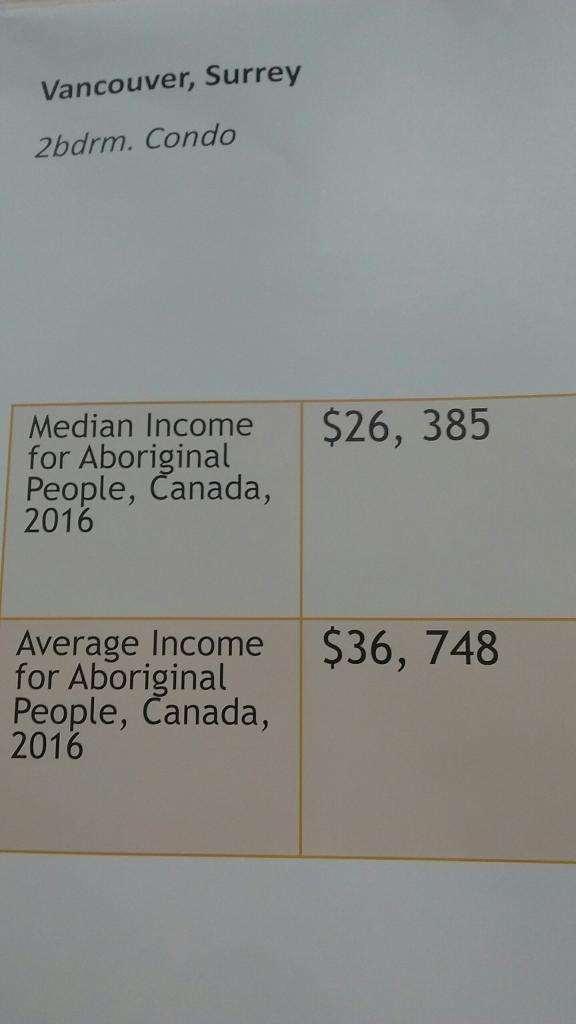

The justice session began, appropriately enough, by stating clearly that the big injustice we all face is that we are colonized. At some point someone colonized all of our families. It was pointed out that injustice comes first in thinking about justice for Indigenous people, on the basis of the very fact of colonialism. That injustice also includes, but is not limited to: racism; homelessness; children in care; education; inequality; government structures; the justice system. How do justice issues relate to other issues? Well, housing problems for people who have been incarcerated, for example. Colonial justice clearly does not work for Indigenous people, and, it was pointed out, it does not work for non-Indigenous people either. Most are targeted and processed for being poor or discontented.

Norm Leech made the point that people are in conflict with the law, because the law is in conflict with them. The laws were written in conflict with Indigenous people. They are not in conflict with the law, the law is in conflict with them. Leech asked: “When was there justice for Indigenous people?” The answer was straightforwardly: “Before colonization.” So that is what justice would look like for Indigenous people.

It must be remembered too that each nation had their own laws for maintaining care and stability in the nation and care of and with the land. Those laws and systems of justice were developed over hundreds of thousands of years. They were well developed and practiced. In the stories are the laws. Many of these records have been lost because they were not written down. And because those who carried oral learnings were erased through colonialism.

Mainstream society talks about reconciliation but says little about truth. So genocide is not mentioned and the term itself is avoided in mainstream society. Yet Indigenous people focus, rightly, on the truth of genocide. How does one talk about genocide recovery? Genocide is a group process. Community recovery rather than only individual recovery is the central focus.

It was asked if it is useful to fix or propose policy and program changes to “solve” justice issues for Indigenous people within prevailing frameworks? Solutions have been colonial “solutions.” Money, policy, curriculum, positions. Restorative justice is based on Indigenous justice. But it has been coopted in some ways. It was suggested that in consultations people not trust the government. Do not answer their questions. It was recognized that governments, police, etc., will not take information and act in a way that is helpful in meeting peoples’ needs.

People want justice, and they want justice advanced. One respondent suggested doing it their own way without the state’s laws. So these sorts of transformative approaches are being discussed. They are desired by people. And they are realistic. Yet reconciliation approaches tend to marginalize or diminish them, posing them as unrealistic or “out there.”

Culture saves lives. Sharing economies save lives. It was pointed out that these are what are saving people in the fentanyl crisis. Not criminal justice systems, which make the crises worse. In sharing economies no one need be alone. There are responsibilities to the community. But the community also takes care of you. Learning is done in the community, for the community, and in service to the community.

The Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development was raised. It identifies three conditions for economic success. First, sovereignty and self-rule. Second, capable governing institutions. Third, a congruence between institutions and Indigenous political culture. This did not generate detailed discussion or debate. It was pointed out that one cannot be fully self-sufficient and self-reliant if you go to the colonizers for funding.

The colonized system is the problem and every system within it is the problem. Fitting better within that system is not working for Indigenous people. Answers are found in pre-colonization. Five hundred years of experience show that colonial criminal justice systems do not work except for colonial elites.

Importantly, the discussion moved to a consideration of prison abolitionism. There is a need to think about things to do for people targeted by police and the criminal justice system. It can include providing housing for people who have been imprisoned. It requires, more broadly, thinking how to be transformative in developing practices. It requires creating cultures where we do no feel a need to call the police and do not need to. This includes, again, communities of care.

There are some who do real harm, but they are not the ones that the criminal justice system spends most of its time and resources dealing with. They are not even a small minority of people processed by the system. And on the whole there are relatively few examples of extreme evil.

One step in abolition is the decriminalization of illicit substances. The money used on criminalization could be taken out of the criminal justice system and policing and put into social health and well being. Defund the police and support actual caregivers in the community.

Conversations need to be held in communities more. It was suggested that people not ask permission to do what works. Do it according to the needs of the people in question. Do it if it works. This includes doing it under the radar. It is alright to be subversive.

On the whole this was a productive conference. Over almost eight hours a range of crucial issues were addressed. And responses were honest, direct, and often bold and visionary.