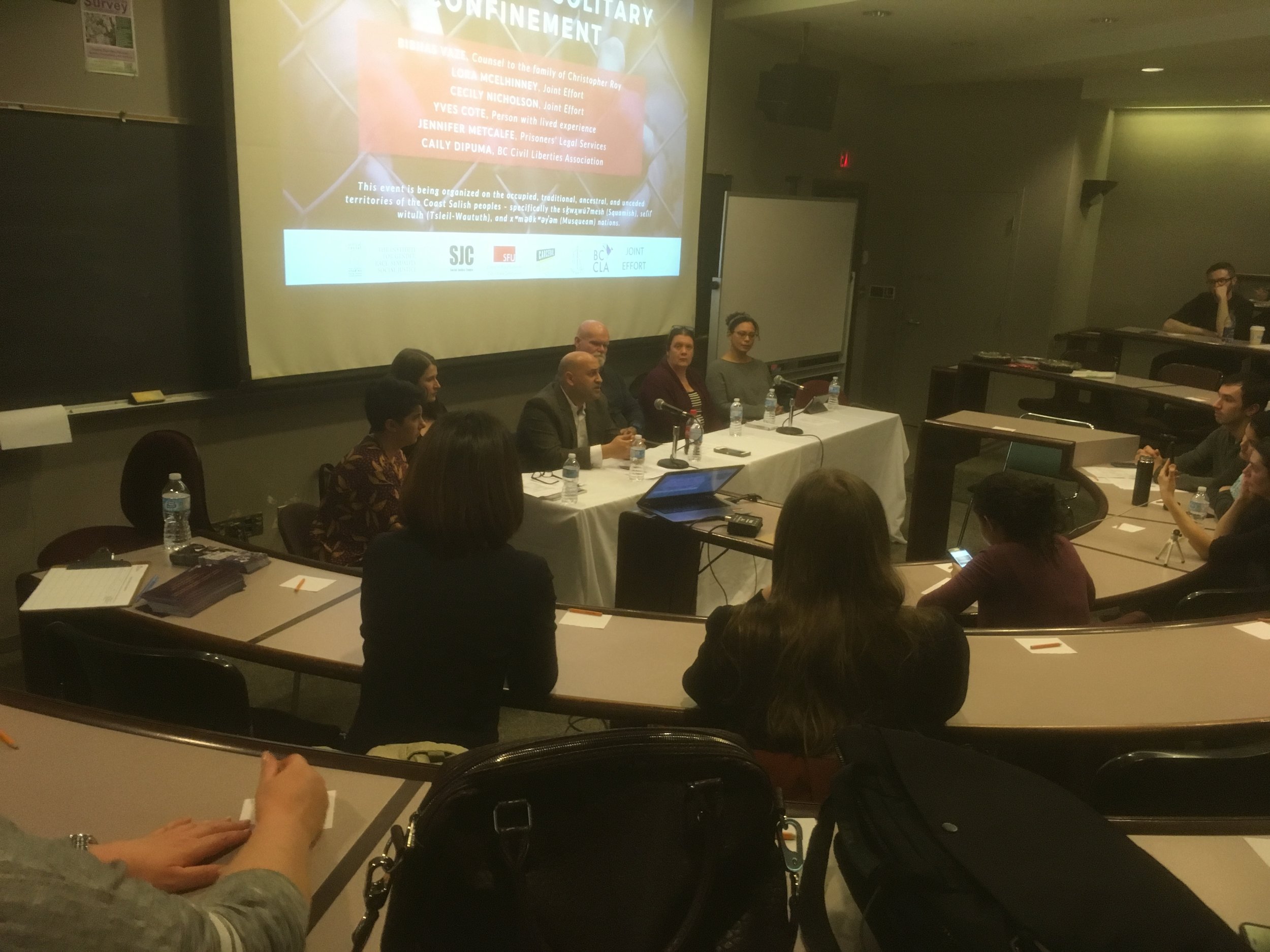

“Challenging Solitary Confinement” A Report.

By Jeff Shantz

On January 17, 2018, BC Supreme Court ruled that the practice of prolonged and indefinite solitary confinement in Canadian prisons is unconstitutional. The decision came in response to a challenge from the BC Civil Liberties Association. In a lengthy ruling, Justice Peter Leask found that the laws surrounding so-called administrative segregation in prison discriminate against Indigenous and mentally ill inmates. On February 6, 2018, a panel of prisoners’ justice advocates, including moderator Caily DiPuma, the BCCLA lawyer who argued the case spoke on issues of solitary in Canada and the implications of the ruling.

The Speakers

The first speaker was Bibhas Vaze, counsel to the family of Christopher Roy, a prisoner who took his own life while in solitary. Vaze is a litigator with 10 years of experience working with prisoners, specializing in law related to incarceration, especially filing habeas corpus. He started by saying that in his work he assumes that prisons do not cooperate. It is not a cooperative process.

Notably, Vaze was clear that rule of law does not really exist within prison. He said that in working on cases he expects that at some point he will have to go to court to bring rule of law within prison walls. Positive decisions are never enough. He noted that there is a history of legal decisions that are not brought within prison walls—there is a fundamental non-compliance with the law. Supposedly great laws are often not applied in prisons.

Vaze told the audience that it is necessary to understand that prison administration and solitary have to be thought of as a whole. Prison cultures work through competing interests—and these are not the interests of the prisoners.

Vaze reflected on his work with the family of Christopher Roy. He noted that in the inquest into Roy’s death it was reported that there was no mental health staff for segregated inmates. Non-qualified psychologists and social workers did assessment on him and found no risk—shortly before he killed himself. There was no time provided for release. Instead he was threatened with transfer to Kent, a more violent institution. In fact they served him papers on the transfer at his segregation cell. Two hours later he was found hanging in the cell. There were no qualified medical personnel at the institution to revive him.

Vaze emphasized that in Roy’s case the existing laws could have been followed—they were not. It was not a problem of the absence of laws, but the absence of compliance.

The second speaker was Lora McElhinney of Joint Effort. Joint Effort is an abolitionist group started by a prisoner on Prison Justice Day forty years ago, From an abolitionist perspective they look at the capacity of communities to provide resources that people might benefit from in prison, including specific programs. Their view is that these programs can be better provided in and by communities. Prisons do not serve either communities or prisoners.

McElhinney suggested that segregation is the worst of the worst, but everyone in prison suffers in various ways. These include the decline of mental health. Prisons overlook or downplay root causes.

It was noted again that in prisons policy takes over from law and arbitrary decisions become the order of the day. Policies become more labyrinthine and keep the community out and the prisoners in.

Cecily Nicholson, another Joint Effort member, acknowledged the fugitivity that is part of everyday practice in the downtown eastside of Vancouver. She spoke to the gendered aspects of punishment and the reproduction of trauma in women’s lives. Nicholson emphasized the disproportionate racialization of imprisonment. Indigenous women do harder time. They do the majority of solitary. They are subjected to more maximum security placements. And they are subjected to more use of force interventions.

Nicholson stressed the inherent cruelty of prisons and reminded the audience that it is an outcropping of genocidal policies. While the Justice Minister makes a push to “Indigenize the prison system,” Nicholson noted, following a recent tweet by Ryan McMahon, that community supports and resources are more needed and helpful than Indigenizing the prison pipeline, which remains a system of cruelty.

Speaking next was Yves Cote,a person with lived experience in prison, and i solitary, serving two life sentences. He noted that he has experienced every level of incarceration. Cote argued that worse than segregation is transfer out of province, away from family, friends, connections, and communities. Yet the Correctional Service of Canada is thinking about using that as an alternative to segregation.

The final speaker was Jennifer Metcalfe of Prisoner’s Legal Services. She expressed excitement about the decision and the possibilities it raises going forward. She is optimistic that they can change the culture. Metcalfe told the audience that her group has received reports from prisoners of guards slipping razor blades under cell doors of people at risk of self harm. They have heard multiple reports of this from multiple people.

The brutality of prison guards and their central role in resisting reforms was noted by all speakers. Metcalfe spoke of pushback from guards’ associations who want to be able to use solitary. It is a matter of convenience for them.

Question Period

The question period was also fruitful and a number of issues were given additional attention. It was generally agreed that in the short term there is a need for a culture shift from all involved in the prison system (health care providers as well) to break them from the corrections mindset. It was also suggested that a change federally returning to a Conservative Party of Canada government will make that impossible.

It was reiterated that guards and staff associations have been the major part in keeping solitary in place. They have, in fact, gone to great lengths to maintain it. It is more convenient for guards and it takes fewer resources for the prison system. Priority is placed on staff comforts and resource costs. These are not reasons for abuse of people. And guard associations are not properly unions and really have no place in the labor movement.

It was pointed out that as bad as federal prisons are, provincial prisons operate behind closed doors. No one is looking inside them. They are out of control. Levels of brutality are high and unobserved outside. It was noted that one cannot even FOI data because they do not even keep it.

McElhinney stressed that cultures like those of prison administration have to be forced. They do not shift on their own or voluntarily.

DiPuma concluded by reflecting on the limits of what she does as a lawyer. It was pointed out that under Section One of the Canadian Charter the government can justify their reasons for restricting human rights. The court will decide if the reasons are legitimate.

Vaze noted that Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 did not de-segregate schools in the United States. Much of the work of the NAACP over the next 50 years was going to small districts and ensuring that the decision was implemented. And this was also in a context of civil rights movements.

Conclusion

Justice Leask said the existing rules create a situation in which a warden becomes judge and jury in terms of ordering extended periods of solitary confinement. He wrote:

“I find as a fact that administrative segregation … is a form of solitary confinement that places all Canadian inmates subject to it at significant risk of serious psychological harm, including mental pain and suffering, and increased incidence of self-harm and suicide.”

The reality for prisoners right now is unchanged. The court gave the government 12 months to draft new law that meets the Charter.

All panelists were in general agreement, even the abolitionists (and I consider myself one), that the decision on solitary is an important one. McElhinney said that while an abolitionist she was still excited about the decision. It ahs opened spaces to talk about abolition and prison harms and the work that needs to be done. But it is only part of a wider goal. The judgement must be subject to a longer view.

Abolition will not come through litigation. We do need multi-level approaches to get to abolition. And as criminologists it means we have a responsibility to teach and work toward abolition. Criminologists must reject the conversion of their departments into recruitment centers for the prison industrial complex. We must oppose the intrusion into our departments by police, prison guard recruiters, and border security agencies. This means rejecting their presence in the classroom, in co-op programs, and at job fairs on campus.

The public still has much to learn about what goes on in prisons every day. There is a need to expand the discussion to talk about everything, not only the high profile or “hot” topics. In response to a question about why it is that prisons have been repeatedly non-compliant without any consequences, Cote pointed to the demonization of prisoners in the public. The public says lock them up and throw away the key.

Regardless of laws and oversight it will only be as effective as people are willing to advocate for. And change requires persistent mobilization and conscientious vigilance.