A Report on “Let’s Pull Brazil Out of the Red: Belligerent Obscurantism and the Political Relevance of Critical Studies,” a Public Talk by Newton Duarte, full Professor in Psychology of Education and Pedagogical Theories at University of Sao Paulo State, Araraquara, Brazil.

SFU Harbour Centre. Co-sponsored by SFU's Institute for the Humanities, Global Communication MA. Double Degree Program, and School for International Studies.

By Jeff Shantz

The rising tides of reactionary politics, authoritarianism, Rightwing violence, and corporatist governance have been facilitated and managed through attacks on knowledge, understanding, and critical thinking. Indeed, even basic social facts (poverty, racism, climate change) have been deniedin a barrage of fake news and alternative facts by spokespeople of the Right (Trump and his surrogates on mainstream news) and neoliberal bureaucrats. Part of this attack has been and is being carried out too by higher education administrators and faculty in the service of converting education into prep for the labor market and the university into an edu-factory (organized according to the demands of state and capital).

Newton Duarte refer to these attacks on critical studies as belligerent obscurantism, an apt term that highlights the contempt for critical thinking and scholarship and the aggressiveness of the assault and arrogance of those promoting it. On Friday, September 8, 2017, I attended an insightful presentation on the current context of neoliberal education, recent policy shifts, resistance, and the role of critical thought given by Duarte through Simon Fraser University’s Institute of Humanities.

Neoliberalism and Austerity in Temer’s Brazil

Duarte begins his analysis with reference to something of a double entendre by current Rightwing Brazilian President Michel Temer. In October 2016 Temer used the slogan “Let’s Pull Brazil Out of the Red.” This had a double meaning. On one hand was an economic meaning around social spending cuts and debt. On the other hand it was an attack on the Left (the “Reds”) and specifically the Workers Party. At the same time the government introduced a new wave of austerity legislation.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights called the legislation a violation of Brazil’s obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights. The Rapporteur called it a radical measure putting Brazil in a socially retrograde category. Temer’s Rightwing government is returning Brazil to a position as one of the most unequal countries on the planet according to Duarte.

“Let’s Pull Brazil Out of the Red.” This was a declaration that Brazil is being put in service of the global financial system and opposing workers’ policies and programs.

In February 2017, the Brazilian national Congress imposed change in the education system so students could vote on educational emphasis. Their limited choices would include: preparation for labor; language for technology; and math for technology. This legislation confines education within limits of neoliberal frameworks. It is geared to prevent (not discourage but prevent) critical and reflective worldviews inside the schools. In prime doublespeak fashion the education law is posed as freedom of choice and modernization for students.

The attack on critical thinking is also an attack on workers in favor of capital. On July 11, 2017, the government introduced a Labor Reform Bill. In it, enterprise agreements take precedence over laws. There is an end to compulsory trade union contributions. There are also restrictions on the scope of decisions of the Higher Labor Court. This legislation has been much favored by employers’ associations.

The Chamber of Deputies approved a text enabling businesses to sub-contract all of their activities, not only secondary ones. There are fewer protections for workers and worse working conditions are allowed.

The argument used by government and employers is that relationships between workers and capital are now more flexible (a longstanding neoliberal catchphrase). Well, the minimum time for lunch used to be one hour. Now workers can get only 20 minutes. That is certainly more flexible. Work contracts can sign away health and safety protections as doing so is more flexible.

Duarte notes that all of this is being imposed alongside a demonization of Leftists, communists, and “Red” ideas more broadly. Red is being associated with the devil in Brazil. People are attacked on the street for wearing red.

Mass protests were met by acts of social war by the Temer administration. Use of extreme violence was made to put down protests. In response to student occupations the government cut off water and energy to the schools. According to Duarte, police used helicopters to drop bombs on teachers in protests.

Belligerent Obscurantism and the Edu-Factory

This is part of concerted efforts to silence critical faculty at all levels of education. There is a movement in schools to denounce teachers who seek to develop critical thinking. Any critical analysis of social problems created by capitalism is considered to be “indoctrination.” It is not, however, considered to be indoctrination to promote the uncritical acceptance of the status quo and its worst elements (poverty, authoritarianism, repression, punitive institutions, etc.). Critical analysis can be labelled communism and teachers can be banished from the schools (even as promoters of exploitation, colonialism, white supremacy, remain). Only certain facts, altfacts, may be allowed (but they are not factual because they exclude important understandings).

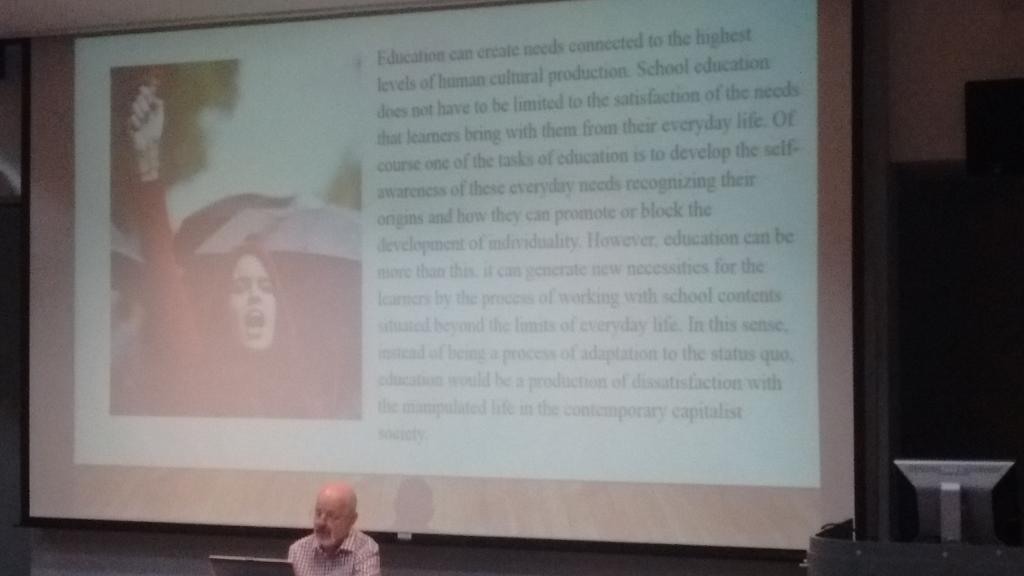

Concerted efforts are being deployed by governments, corporations, and school and university administrators to change curriculum so that it is more adapted to demands of the market. Education is being used primarily to prepare students for neoliberal labor and to adopt themselves to any changing situation (downsizing, unemployment, speedup, flexibilization, automation, etc.). The push is to not teach knowledge and understanding but to teach students to adapt to new and changing situations in a labor market or state regime directed by others. So classes in theory or history or analysis get taken over by classes in professional behavior or interpersonal relations within the workplace. And these take up a greater proportion of course offerings.

Obscurantist models insist: Develop skills that make student-workers ready for unpredictable situations. Do not prepare them to change reality. Prepare them to adapt to changing reality. Prepare them to fit in. Prepare them to take a place. Higher education is put in the service of the market. Students are taught to adapt to service in the market or the state. Not knowledge. Not thinking.

As Duarte suggests, the market decides. He says the market is like a god. But it is hard to know what gods want. They keep their secrets. Also, gods want regular sacrifices. Student-workers are sacrificed in the market.

Notably, Rightwing governments are emboldening Rightwing forces, including forces of violence, on campuses. So too are administrators upholding these neoliberal, market authoritarian, models. This creates and supports conditions for going after critical faculty (by altRight vigilantes or administrators). There are real threats to critical faculty losing their jobs or being harassed out of their positions.

The altRight demonizes education in general. The altfacts altRight fears full knowledge. They wasn’t schools as sites of entrepreneurship, “skills,” etc. They know education can be a potent force for social change. And neoliberal administrators are giving them what they want.

Critical Studies Against Belligerent Obscurantism

For Duarte, we need to develop critical resources to organize the struggles against this belligerent obscurantism. There is a pressing need to defend knowledge. The Rightwing is doing the opposite. It is promoting obscurantism. We need to defend schools as spaces for developing and sharing humanity’s best knowledge.

Education is not simply about the transmission of everyday life facts. It promotes the transformation of everyday life. As Duarte suggests, it turns water into wine.

While education administrators turn to “student evaluations” to gage faculty competence (often on the basis of ease or enjoyment), Duarte reminds his audience that education and learning are not merely pleasurable. They may in fact be disturbing and upsetting. They may, and should, challenge your assumptions rather than simply reinforcing your base prejudices and assumptions about the world.

Education is not only a transference of information from one person to another, but a transformation in the way that we see the world and ourselves. This translates with the development of our worldview and our personality, as Duarte emphasizes.

If Temer says “Let’s Pull Brazil Out of the Red,” with critical education the Red can be brought back to Brazil’s situation for Duarte. To promote other perspectives. To promote the critical analysis of reality. Duarte calls for a fight against belligerent obscurantism everywhere. And in the current period of fascist rising we face belligerent obscurantism everywhere.

All of us involved in social justice education and critical pedagogy should pay serious attention to all of this. And act against it. We are in no way safe from such attacks in the Canadian or US context as Rightwing attack lists of critical faculty, administration harassment of critical faculty, and the marginalization of critical studies and privileging of oppressive “administrative” models within programs like criminology show.