By Jeff Shantz, March 12, 2020

Cyberwar and Revolution: Digital Subterfuge in Global Capitalism, by Nick Dyer-Witheford and Svitlana Matviyenko examines the parts played by digital platforms within various global uprisings recently, both by insurgents and by states and capital seeking to co-opt, contain, manage, and/or extinguish resistance.

Influenced dually by autonomist Marxism and psychoanalysis, the book gives extended attention to the political economic and psychological aspects of cyberwar. Capitalism and the militarization of the Internet serve as foci shaping the book’s arguments. And resistance and organizing against this militarization. Released in 2019 it claimed the Science, Technology, and Art in International Relations (STAIR) Award of for that year by the International Studies Association (ISA).

http://www.sfu.ca/humanities-institute/public-events/archive/2019-20/cyber-rev.html

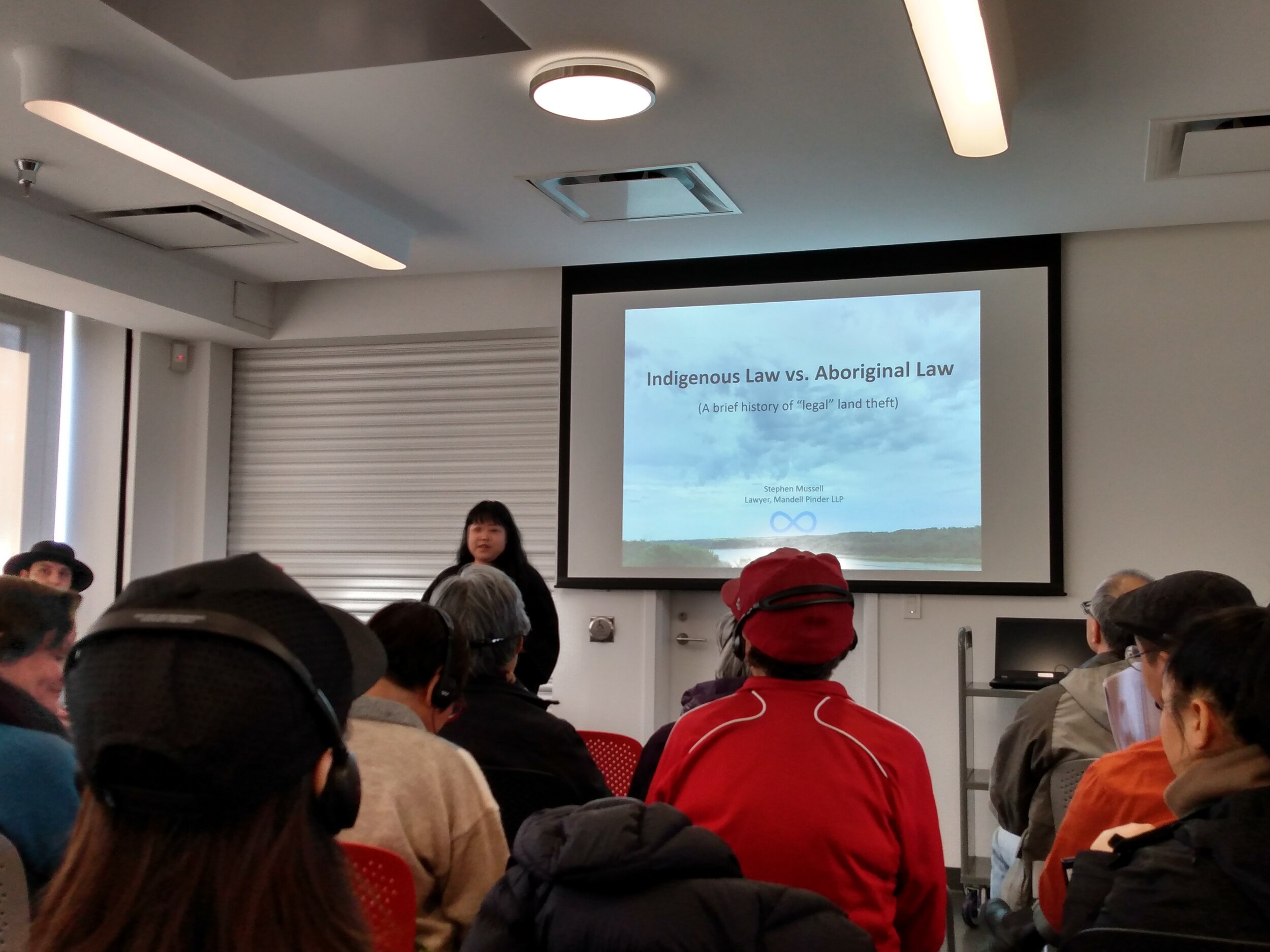

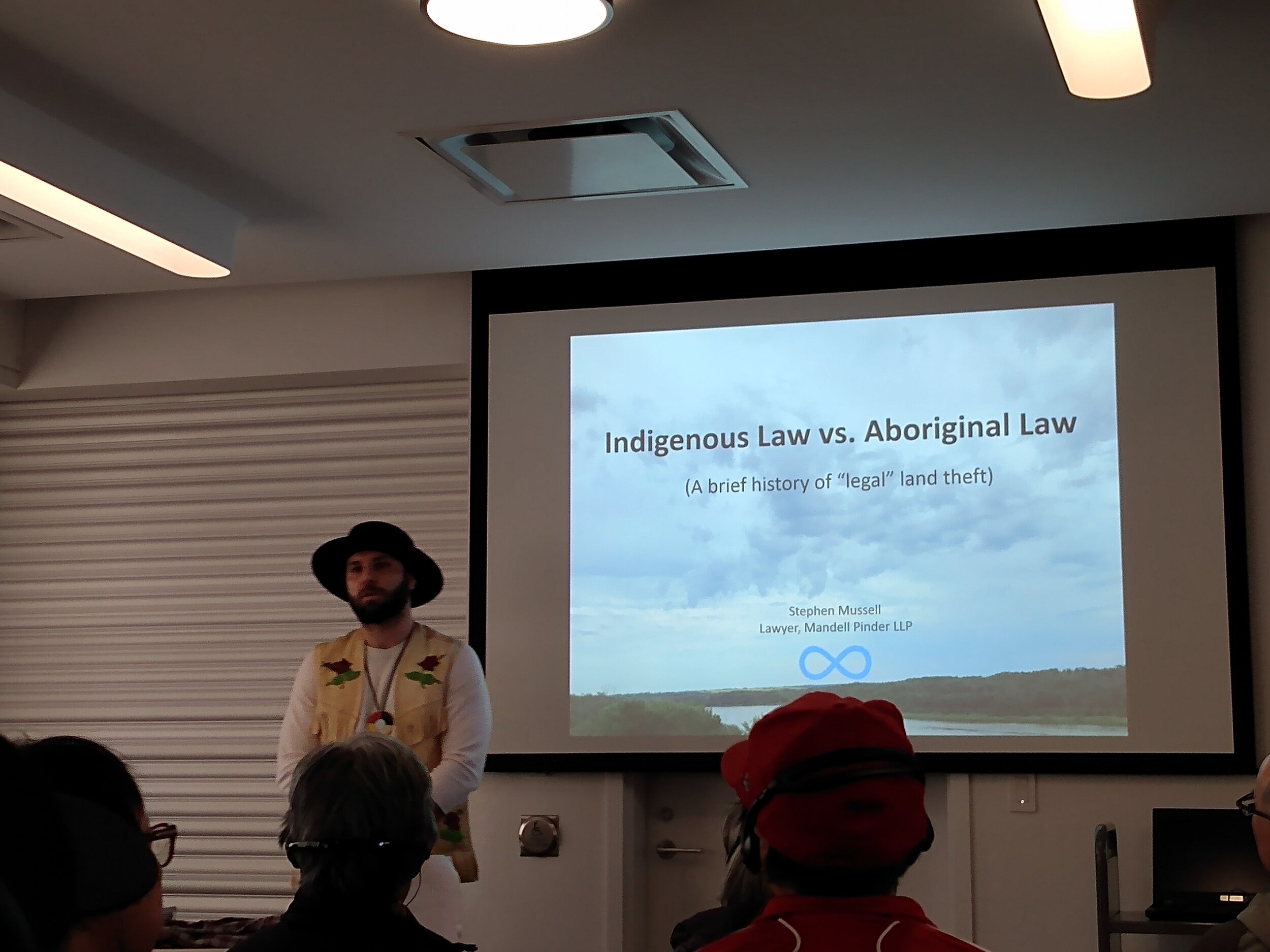

On March 6, 2020, the authors provided extended discussions of the book, with added commentary by Samir Gandesha of the SFU Institute for Humanities. Hosted by Zoe Druick, the discussion was a session of the Book and Speakers Series in the School of Communication at Simon Fraser University.

Their respective talks were outlined as follows:

Dyer-Witheford: “Cyberwars and Riot Platforms.”

Matviyenko: “There Is No Fake News.”

Gandesha: “Is There a Cyber Fascism?”

Cyberwars and Riot Platforms

Dyer-Witheford began his portion by relating that his presentation involved reflection on the book along with the start of a new project on riot platforms. He noted that much of this recent work involves a rethinking of popular conceptualizations of cyberwar. Cyberwar has been conventionally thought of as consisting of mercenary hackers, digital infrastructure attacks, etc. within a New Cold War of intercapitalist state conflicts—between, especially, the United States, Russia, China, Israel, and Iran.

But, Dyer-Witheford stresses, there is another aspect. Alongside interstate cyberwar are the cyberwars waged by states against the populations they rule over. This involves surveillance, repression, force, especially against social movements

These struggles have been on display in the period of widespread unrest from 2018 to today. The sites are numerous, including Hong Kong, Paris, Quito, Beirut, Barcelona, Tehran, and Baghdad, among others. Dyer-Witheford assembles characteristics of these large protests. Some of these are violent clashes that have been sustained over weeks and months. They have been marked by actions like protesters in Santiago using blinding lasers to repel riot police, as Dyer-Witheford showed during his presentation. In Chile, more than 100 Walmarts have been torched, he notes. These are intersectional movements against inequality, precarity, corruption, and brutality according to Dyer-Witheford. He asks if these uprisings constitute global revolt against neoliberalism.

In attempting to answer this question, Dyer-Witheford turns to the work of Joshua Clover, and in particular his book Riot, Strike, Riot. In that work Clover contends that production under capitalism Is now superceded by circulation. The viable form of protest, then, is no longer the strike—it is the riot (the interruption of circulation). Actions in this context target streets, trains, ports, airports. These are struggles against circulation. And they are simultaneously the circulation of struggles. This includes, and this is a focus of Cyberwar and Revolution, the use of online platforms and social media to circulate and mobilize.

Dyer-Witheford outlines “three pulses in one cycle of digitized struggle.” These are: 1994-2001. The alternative globalization movements. Digitized struggles innovated forms through Indymedia; 2010-2014. Occupy which innovated the assembly form. 2018-Now. The urban uprisings.

The present struggles show the significance of what Dyer-Witheford here calls Riot Platforms. This involves the use of digital platforms to organize sustained struggles. He is careful to stress that these platforms are not the cause of the struggles. They are tool.

There are also, of course, corporate platforms, such as facebook, youtube, and twitter, which have been used to incubate and circulate protests. Dyer-Witheford notes that powers of panoptic observation have not been enough to stop the sue of these corporate platforms to circulate struggles.

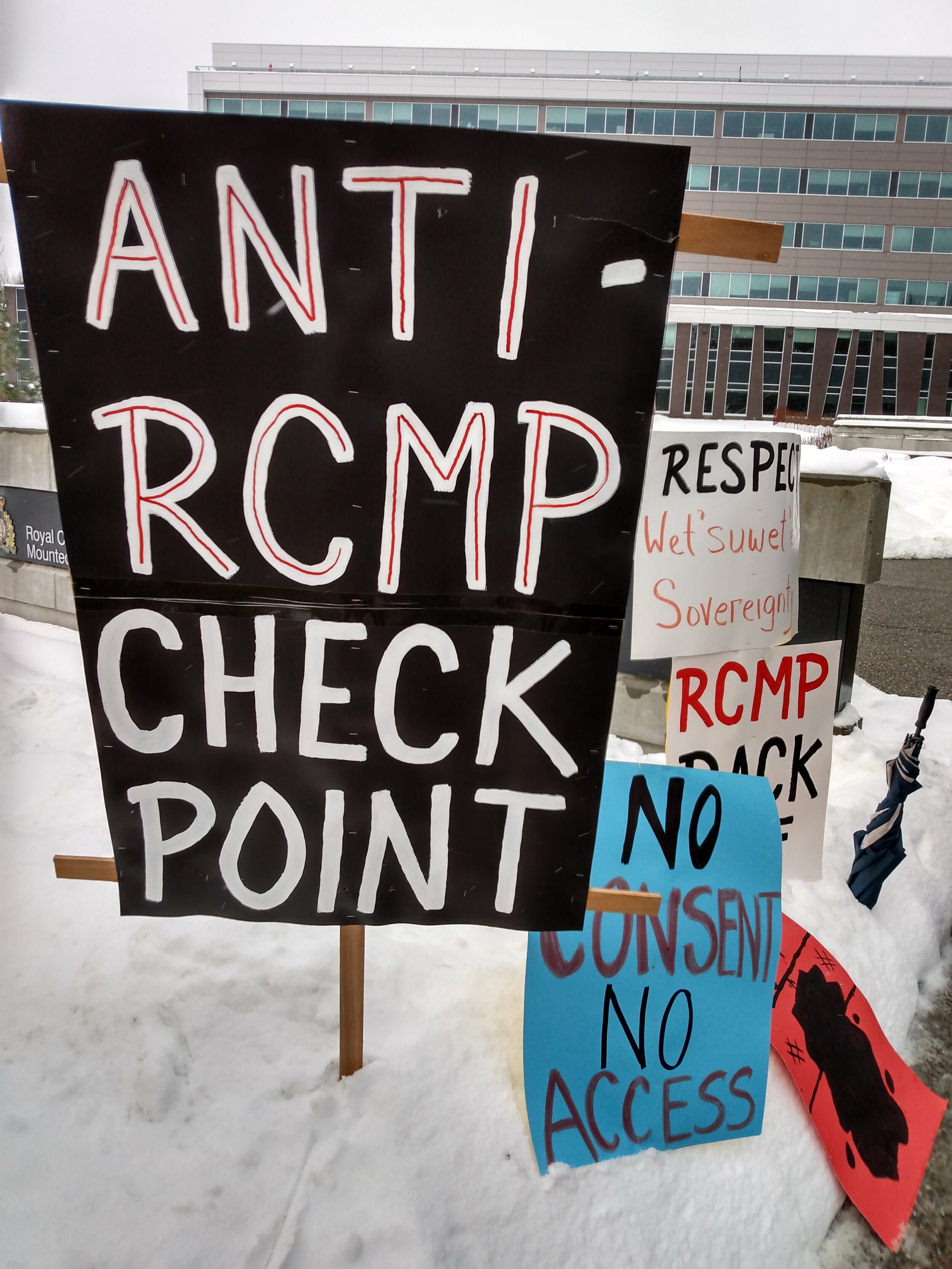

Other aspects that Dyer-Withford identifies are struggles against surveillance, including the use of lasers, masks, and face painting. There are also efforts to “dismantle the smart city,” such as breaking CCTV cameras. Activists have also pursued acts of sousveillance (surveillance from below, watching the watchers). These include de-anonymyzing police and documenting police brutality. Activists have also used encryption apps, such as Signal, Telegram, and WhatsApp.

Security forces have counter-attacked with blackouts, infiltration, and disruption, including blackouts targeting encryption apps.

Dyer-Witheford argues that in the current cyberwar there are deeply violent events at levels approaching civil war. Domestic protests are blamed on foreign states, while states instigate protests in those same foreign states.

Dyer-Witheford’s presentation concludes with a discussion of transnational aspects of uprisings. There is a significant development and circulation of struggles outside of the interstate conflicts. The revolts are connected across diverse locations.

He suggests that riots may not be enough, but they will be necessary. There is also playing out in all this a rift on the Left between the uprisings and movements prioritizing Left populist electoralism (as in the campaigns of Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders).

There is No Fake News

In her presentation, “There Is No Fake News,” Svitlana Matviyenko shifts the focus toward a discussion of so-called fake news and debates around the notion. She begins by reminding the audience that using fakes for political purposes has a long history. Indeed, the more cynical among us might suggest that fakery is the character of liberal democratic politics under capitalism. Matviyenko notes that the notion of fake news is of recent coinage. Yet, fake news is no different from ads—the very tool of circulation in consumer capitalism.

How might one define fake news, she asks. Bias, sloppy journalism, propaganda? Some or all of these? Instead of “what,” perhaps we need to ask “how,” she suggests. And how does it relate to cyberwar?

Matviyenko claims that fake news is a play or move within a larger game of cyberwar. Cyberwar is situated as recurring technological revolutions by which capital renews itself. This has gone by such names as “third industrial revolution,” computer revolution,” “information revolution,” or “cyber revolution.”

To bring the discussion together Matviyenko employs the notion of Communicative Militarism. It involves the micro-targeting of markets. The imagined boundary between commerce and war collapses along with the imagined boundary between ads and fake news.

Cambridge Analytica was infamously used as a data war/psychological warfare tool, psy-ops, during the 2016 campaign for president in the United States. Matviyenko reminds the audience that data was used from a personality test facebook app with 87 million people involved, most from the US. As punchline, the CA whistleblower went on to lead AI research at fast fashion giant H&M.

Matviyenko claims that what we are seeing is a fusion of capitalism and militarism (perhaps at another level, since I would argue that that fusion has always been there, and histories of colonialism tell us this). Yet what is viewed as evil in politics is viewed as good in capital.

As an illustration of current processes, Matviyenko suggests that Trump’s call to Ukraine about Hunter Biden, the subject of the impeachment, reveals something. President Zelensky says he learned from Trump and his campaign’s “skills” in winning his own election. Zelensky gave no interviews, had no debates during the campaign, His view was that the candidate should be a blank screen on which to project messages. His only appearances were, tellingly, Instagram posts. They showed him jogging and having dinner with families.

Is There a Cyber Fascism?

In asking, “Is There a Cyber Fascism?” Samir Gandesha starts by saying that not only the death drive, Thanatos, but Eros, drove the spread of the internet. He then asks, “How has erotic spectacle played a part in the return of fascism?”

The focus on, and in, Cyberwar, in his view, avoids the return of fascism (which I would add is a key part of ongoing social war). Using ana analysis drawn from Rosa Luxemburg and Walther Benjamin, Gandesha says that militarism and violence arise from the acceleration of technology without democratization of technology.

Neoliberalism, he points out, likes to claim that it has done away with authoritarianism. But—it is internal to neoliberalism (not merely external). Authoritarianism today sees forces coincide—9/11 and the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan; the 2007/2008 financial crisis and “too big to fail” bailouts. Related to these are migrant crises, financial insecurity for the working classes, the rise of Trump, etc.

Political figures like Trump and Stephen Harper, closer to home, bring economic anxieties out in the forms of real people—”concrete others like migrants, in Gandesha’s view. The other is made responsible for “your” troubles by far Right political figures. Fascism, he notes, has always made explicit what is implicit.

Emotional and psychological crises are part of the emergence of fascism. There are subjective, not only material forces. Fascism displaces class analysis and can effect a connection of the precarious, whether lumpen proletariat or petit bourgeois.

Referencing Theodor Adorno’s work to address the authoritarian aspects of neoliberalism, Gandesha suggests that the political agitator is an enlargement of the subject’s own personality. Fascist leaders are “Great Little Men.” The Great Little Man” is only one of the folks. A billionaire who puts ketchup on his burnt steaks, as Gandesha puts it. They do not try to define the nature of discontent by rational analysis (a failing of some who oppose fascism). They disorient the audience.

Love of the leader is a means to overcome negative self-image. This plays into narcissism. What one is/what one should be/what one has been promised but not been delivered.

Today, and returning to themes of cyberwar, algorithms reinforce repetition and stereotyping. Key parts of the authoritarian personality as delineated by Adorno. Social media allows agitators to move around institutional critiques. There is an “accelerated circulation of negative affects”—click bait.