March 8, 2020

By Jeff Shantz

The Wet’suwet’en defense of their land against invasion by the RCMP in the service of Coastal GasLink and their planned natural gas pipeline, and the solidarity actions that have sprung up internationally in support of Wet’suwet’en, have sharpened focus on the colonial nature of “rule of law” in so-called Canada, as well as elevating calls to recognize Indigenous law.

On March 6, 2020, the Carnegie Centre Action Project (CCAP) hosted Stephen Mussell, Plains Cree Metis, a lawyer and board member of Pivot Legal Society, to discuss “Legal Land Theft: The History and Development of Aboriginal Law in BC, the Power of Indigenous Law” as part of their legal education workshop series. Mussell gave a compelling overview of what he identified as the racist and shaky legal foundations on which Canada came to be as a state. He illustrated various ways in which the Canadian state did not even follow its own laws in taking Indigenous lands—despite their self-satisfied claims to rule of law throughout (including in the present).

Mussell started with a brief biography in which he told the audience of 50 or so people that he became a lawyer only to help his people. And he noted that the legal system in Canada has made that very difficult—even more than he thought it would be. Mussell related that he was the first person in his family to finish high school let alone go to law school, stressing the structural inequalities that are only heightened by expensive law school tuitions and exclusive cultures within legal professions. He now works at Mandell Pinder LLP, a firm that deals exclusively in supporting Indigenous rights.

Mussell began by pointing out that the picture on his introductory slide is taken from his home area outside Batoche on the Saskatchewan River. This, he noted, was where his people made their “last stand, so to speak” at the Battle of Batoche at the end of the North West Rebellion. Mussell started here to remind the room that this is land that was stolen militarily.

Indigenous Law: Not State Law

The presentation proceeded through several specific discussions. The first was an overview of Indigenous law and the many sources of law historically. Mussell emphasized that law is more than the Criminal Code and claims by politicians like Justin Trudeau and John Horgan. And different forms of law are legitimate even though the government tries to say that law looks one way and one way alone.

Mussell then addressed histories of legal land theft. He asked, how the Crown got land and how they justify the taking of land.

The talk then provided an overview of Aboriginal law, which is a state framework, not the same as Indigenous law. This is law in Canada arising from state systems in order to address Indigenous rights in laws. Mussell stressed that this is the state’s system—it is not Indigenous law.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), in fact, recognized that it is significant that Aboriginal law and Indigenous law are not the same. The TRC was clear that they cannot be conflated. Yet, according to Mussell, law firms mix these up all the time. Big law firms (those dealing with corporate law especially) have used “Indigenous law” wrongly to describe what they do. Mussell was clear to state that conflation cheapens Indigenous law. It frames it through state perspectives.

Mussell provides proper focus to the presentation by stating that it is always crucial to remember in discussing matters of law and governance that Indigenous communities were self-governing. They arranged themselves in complex systems of governance with complex laws, practices, etc. Even if those were not written, and even if they were partly erased or lost—Indigenous people remain sovereign. They can make their own laws, make new laws, and change laws. Indigenous systems of governance are very much alive. They are simply not recognized—and reasons for this are clearly related to colonial interests. In Mussell’s words, Indigenous law has been interrupted, but never extinguished.

Sources of Law

To provide some context Mussell notes that there are many different sources of law. He identifies: Sacred; Natural; Deliberative; Positivistic; Customary. All intersect in various ways. States privilege positivistic law, to the exclusion or marginalization of other sources.

Sacred law is shaped by religion, spirituality, relations with a creator, etc. The Canadian Constitution even references the rule of God. Sacred law includes stories that involve warnings, notions of right and wrong, etc.

Natural law is derived from interactions with the world. If you harm the waters and salmon die as a result. You learn not to do those harmful activities.

Deliberative law involves people getting together and talking and making decisions directly. It consists of debate, persuasion. It allows for change over time through changing needs or perspectives, values, etc. Community groups and social movements tend to emphasize deliberative law and seek expanded opportunities for participation and engagement. Participatory democracy in action.

Positivistic law relies on proclamations, rules, codes. These come from positions of authority and powers of enforcement. They are often based largely on fear and threat. In statist societies we are conditioned to believe that this is what law is. It is legitimized as all that law is.

Customary law involves past practices and norms developed on what is viewed as acceptable. Mussell points out that racism has reduced all Indigenous law to this, in a caricatured manner. He is careful to stress that this is not all of Indigenous law.

“Legal” Theft

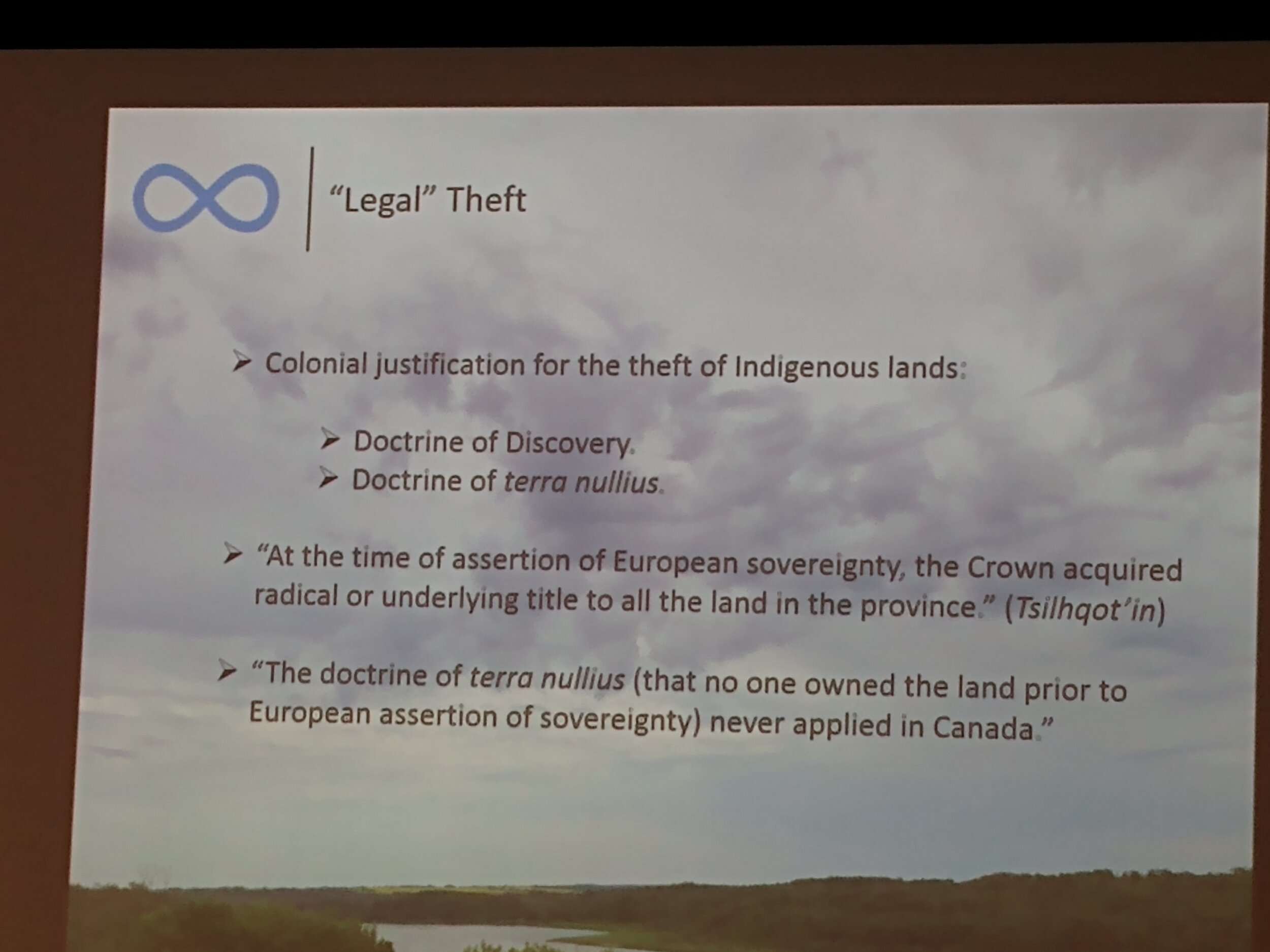

Mussell’s presentation provided a detailed and expansive overview of the colonial justifications for theft of land by the state. This included the Doctrine of Discovery and the Doctrine of Terra Nullius as bases for state claims of title, before focusing more closely on specific legal decisions within the Canadian state.

Very briefly, the Doctrine of Discovery asserted that if no one, or only non-Christians, was on the land, the nobility (as representatives of God on Earth) could claim it. Terra Nullius asserted that no one owned the land prior to European assertions of sovereignty. These were actually political agreements between colonial powers facilitating their divvying up lands they contacted (ie, invaded) Law viewed Indigenous people as less than human. How else, Mussell asks, to claim that “no one” lived in areas that were clearly inhabited? All of this was legal sleight of hand to justify states’ own existence as colonial states.

In discussing Aboriginal law, Musseel highlights Section 35(1) of the Constitution Act of 1982. It says, “The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hearby recognized and affirmed.” Prior to this, rights could be extinguished quite easily. So it offers something of a gain, and Indigenous communities had to fight for it.

Mussell then addressed R v Sparrow [1990] on infringement and justification and R v Van der Peet [1996] on proof. Sparrow concluded that the rights are not absolute. They can be infringed by the Crown if it has sufficient justification. Provincial law could infringe on Indigenous rights. Conservation claims, for example, are often used to limit fishing rights. The Sparrow case itself was over fishing net lengths. R v Van der Peet concluded that rights must have existed pre-contact and must be integral to one’s distinctive culture. It is dealt with on a piecemeal basis. It is expensive and Indigenous communities have to go to court to prove every right.

Delgamuukw v BC [1997] 3 SCR 1010 is at the center of the Wet’suwet’en land defense and has gained renewed prominence as a result of the current struggles. It highlights infringement and the real world impacts of terra nullius.

The Tsilhqot’in decision, Tsilhqot’in Nation v BC [2014] SCC 44, suggests that terra nullius never applied in Canada. So how did the Crown acquire title to all the land in so-called British Columbia? Why did it recognize title claimed by the Crown? It only gave title to five percent of the overall original territory. It does not address waters or self governance. It does allow recognition of title over large areas of land, not only small pieces. Title includes full, beneficial economic aspects. The decision also recognizes issues of consent. If the Crown authorizes projects before title is proven, these projects can be cancelled—after title has been proven.

Infringement is still an aspect of title. The durability of terra nullius is shown in this. It reinforces the presumed superiority of the Crown. Notably, the state can infringe on Indigenous title—not the other way around.

It stipulates the state:

1. Has to consult and accommodate.

2. Has to show a compelling and substantial objective.

And the Supreme Court of Canada gave a list: Agriculture; forestry; mining; hydro-electric projects; economic infrastructure; settlement of populations to support those aims.

So—everything. And all the extractives industries could want. A framework for neo-colonialism.

3. Cannot deprive future generations from benefitting from the land. This is the only vague protection.

Conclusion: Direct Action Propels Change

This was a wide ranging and compelling presentation of issues central to ongoing colonialism via rule of law. Participants were notably engaged and there was much discussion among those present. There were many questions asked and addressed.

Law is not the only, or even primary, ground of struggle. Mussell acknowledged this fact openly throughout. His conclusion, then, was most apt. All the changes that have happened have been driven by direct action and we have to remember that. The actions of land defenders and water protectors show a way toward decolonial possibilities. Right here, right now. And Indigenous youth are playing leading parts in this.