We spent our last day here on the Reforma, Mexico City’s main street, intending to photograph the fabulous art benches that line the boulevards. Along with benches the Reforma is lined with statues commemorating Mexico’s heroes. Every statue has been spray-painted in red with the number “43.” We hadn’t gone far when we came across a tent encampment outside the Justice building surrounded by poster-sized photos of young Mexicans, all with the inscription: “43.” Approaching the camp we noticed a long procession, some of them children, wearing black T shirts and yellow bandanas over their mouths. They marched in single file along the gutter accompanied by the police. Each bandana was printed with a woman’s name: Amy, Eve, etc. A marcher handed us pamphlets and told us they were marching for the 45,000 prostitutes outside the airport.

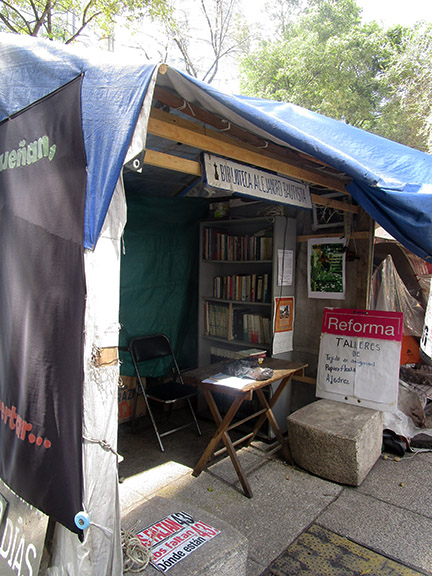

As the procession passed, a woman approached us trying to sell us a crocheted doll with a black hood over its head. In spare English she explained she was a friend of the mother of one of the 43, that the camp had stood vigil outside the Justice building since forty-three students on a bus to Mexico City had been gunned down by the police. People holding vigil for the 43 have lived on the boulevard surrounded by three lanes of traffic on both sides, since 2014. Mexican-style the camp included a central courtyard with its own Day of the Dead papier-mache skeleton and a small library. Donations are being collected in a pickle jar. I asked the woman if she was afraid. She said “no,” and pointed to the Justice building, saying “they are all gone.” Justice has fled the city, leaving an empty building to face the families of the murdered students.

At an exhibition on “ Forensic Architecture” at UNAM: the Autonomous University of Mexico art gallery, we learned from a student docent that the forty-three students shot by the police in the small town of Iguala had been on their way to join an annual protest marking the murder of 10,000 protesters on October 2nd, 1968 in Mexico City. People in small towns are especially vulnerable to attacks by the police, he told us. The story made international news, but in Canada the media didn’t report that the police had attacked people all over the town. The investigation more or less ended with the convictions of the mayor and his wife who was later released. None of the police were ever charged.

Later on our photo walk we came across a black art bench with two upright steel crosses for its back. On one of the crosses someone had scratched: “Nochixtlan June 19, 2016. Fue el Estado” (It was the state).

Back in the hotel we learned Noxchitlan is a small town in Chiapas, the heart of indigenous Mexico, where locals had blocked roads leading to oil refineries to protest the imposition of education reforms by the government of President Enrique Pena. The "reforms" require that teachers re-certify themselves every three years, pass state exams, and don't include curricula or methodologies addressing rural conditions. Losing patience with the protesters the police had simply opened fire, killing nine.

Mexico is a country marked by numbers and dates that are codes for atrocities committed by the state: “June 19,” “October 2nd,” September 26, “43,” “10,000.” If you know the codes you know that the violence visited on the people here since Cortes razed Tenochtitlan back in the 1500's hasn’t really ended. With their crocheted dolls, bandanas, and blockades, they are still fighting the Spanish Conquest.

In Solidarity,