By Jeff Shantz and Eva Ureta, June 2, 2020

The Prison-Industrial-Complex is a continuum—interlinked and interlocking structures of surveillance, repression, displacement, containment, brutality, and death. When we call for abolition, we do not mean only police and or prisons. We mean all of the carceral structures and systems, whether police, courts, and prisons, through to borders and border security. We mean colonialism and capitalism, which the carceral apparatuses serve to protect, reproduce, and expand. The disproportionate targeting and harm inflicted on Black, and especially in Canada, Indigenous people shows what these systems are based on, what they are about.

The uprisings in the United States in response to the police killing of George Floyd, and really in response to generations of anti-Black racism and brutality, exploitation and oppression, have sparked new and expanding calls for abolition against these interlocked carceral apparatuses. They have raised calls for abolition in important ways on some new foundations.

In Canada too, the mobilizing in multiple locales, large cities to smaller towns (like Nelson), has powerfully confronted the realities of anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism in the Canadian state, partly in response to what witnesses have named as the Toronto police killing of Regis Korchinski-Paquet, a 29-year-old Black Indigenous woman. The mobilizations across the Canadian state have brought to the forefront the reality, too often denied or overlooked, of racist police violence in a country founded on settler colonialism, erasure, and genocide.

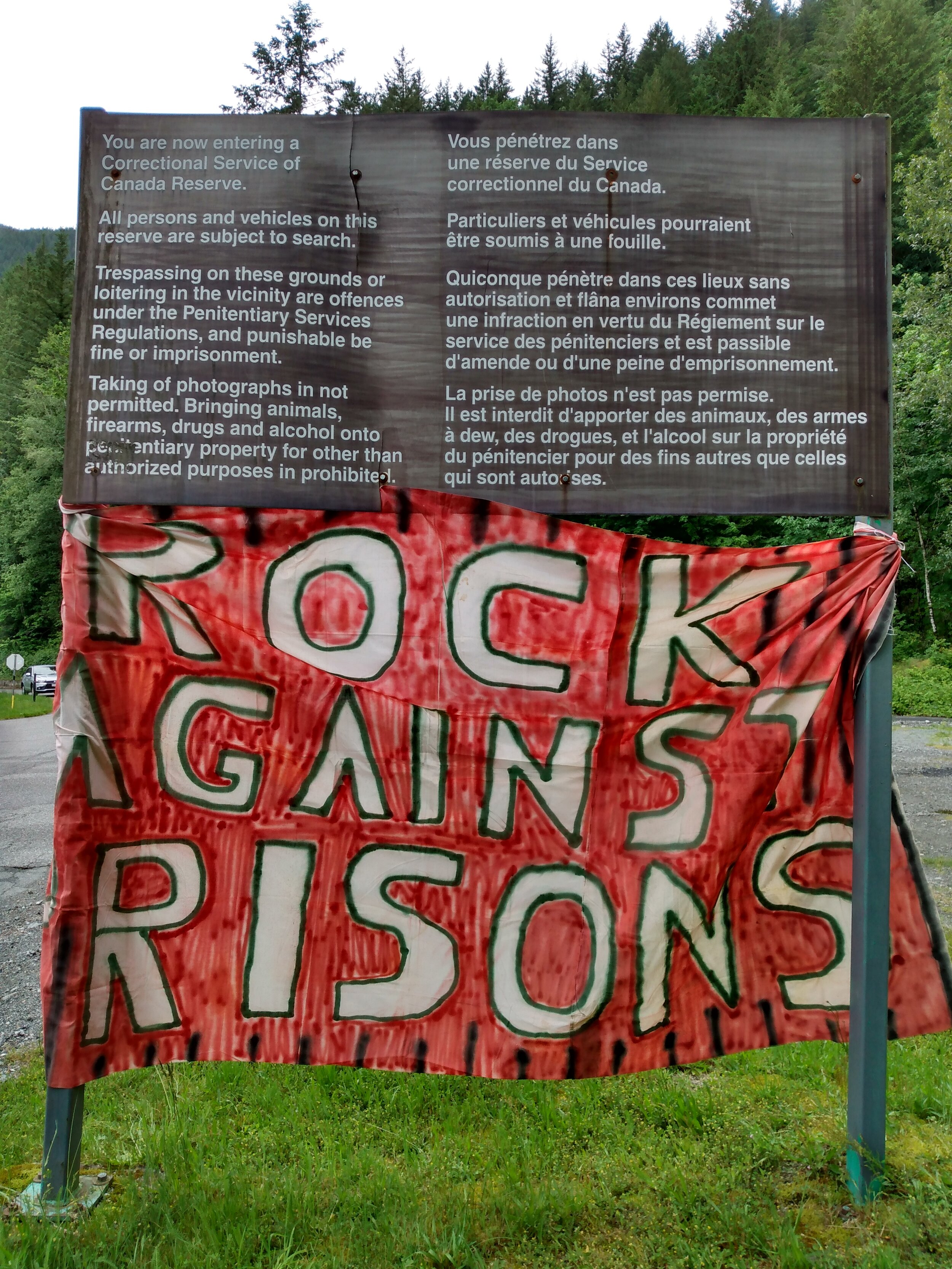

On Sunday, actions as far away as rural Agassiz (unceded Stó:lō territory) and urban Vancouver (unceded Coast Salish territories) raised open opposition to the interlocking carceral structures of violence and control in so-called Canada. In Agassiz, prisoner justice activists and abolitionists took a noise action, caravans making noise outside carceral institutions, to Mountain and Kent institutions. These noise actions have been happening on a weekly basis over the course of two months now in so-called British Columbia in solidarity with prisoners and in recognition of the threats to their lives posed by COVID19 in carceral centers (where multiple prisoners have died and outbreaks have been extreme).

Prisons in Canada are often located in isolated or rural areas. The public does not have to confront the carceral presence. Out of sight, out of mind. Mountain and Kent are in a rural area with farm fields on one side, a mountain and mining enterprise on another. Access to the sites was difficult, as it is meant to be. Out of sight…

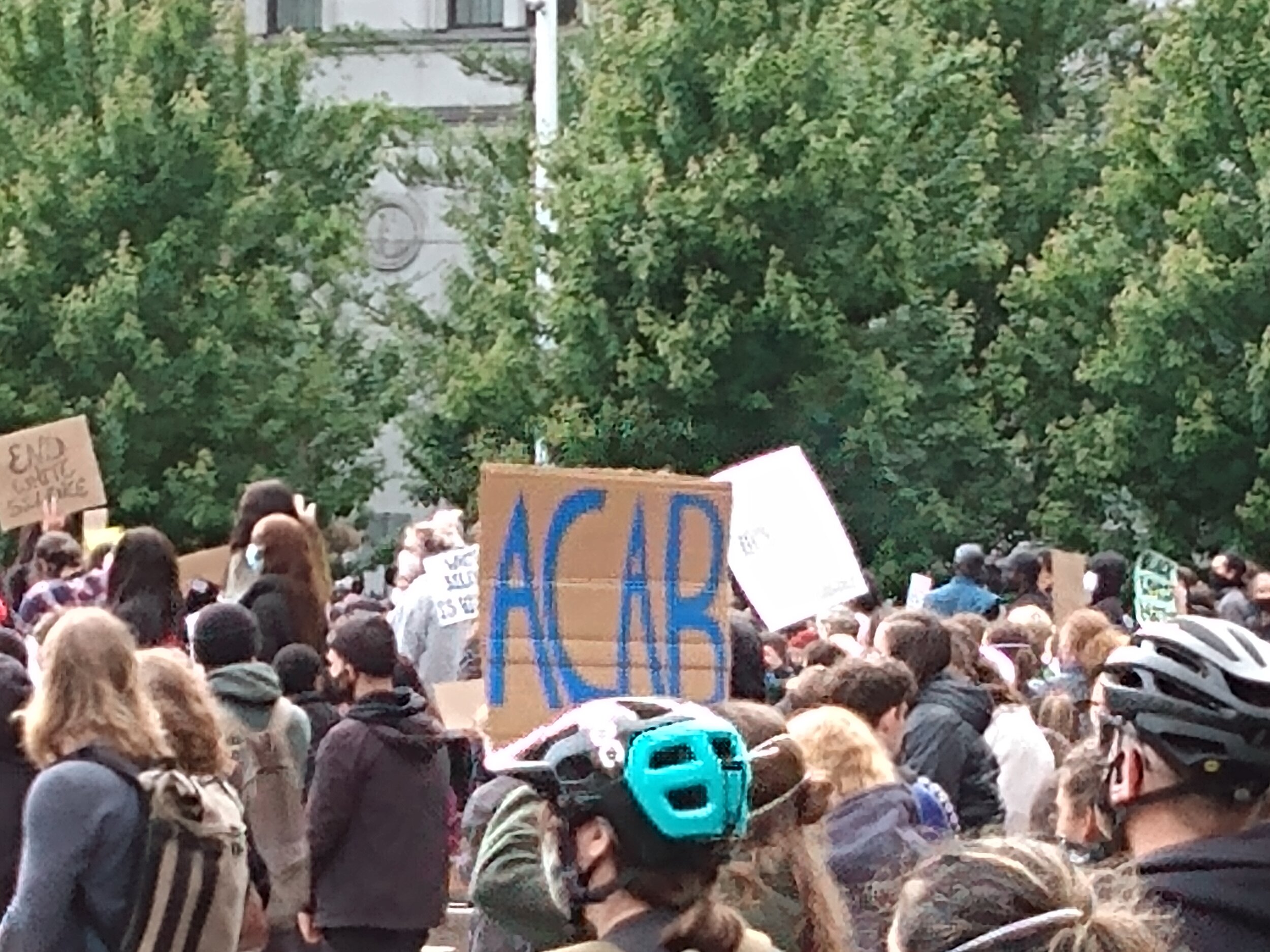

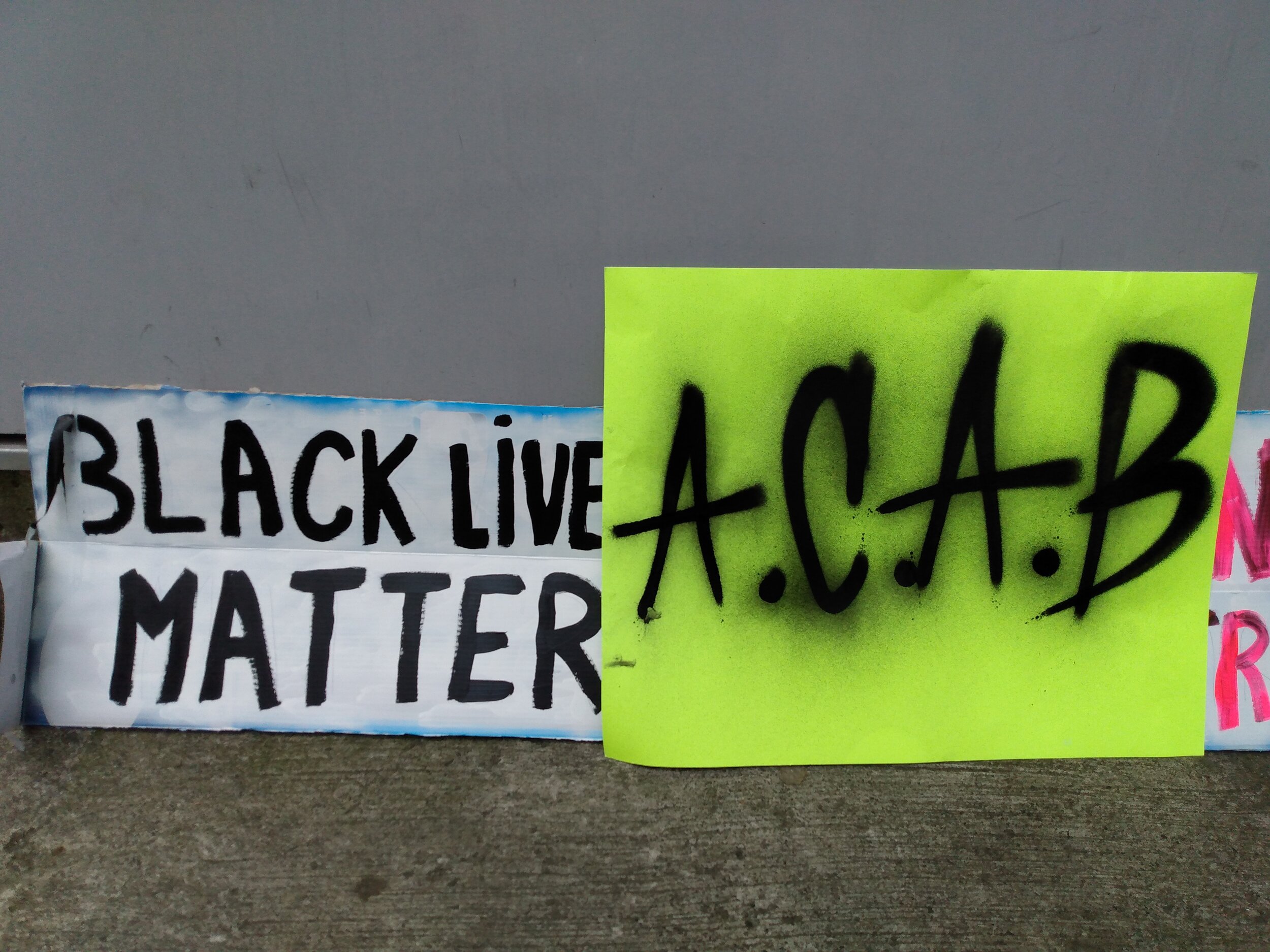

Later in the day folks from the noise demos participated in rallies affirming Black Lives Matter and against policing in Vancouver and in the smaller city of Maple Ridge. In Vancouver, approximately 5,000 people gathered at the Vancouver Art Gallery, where Black residents spoke of their own experiences of racist policing in the city and beyond and raised the calls, “Black Lives Matter” and “No Justice, No Peace, No Racist Police.” Powerful voices, many from young people.

The carceral structures are connected. And the struggles against them, and for abolitionist alternatives, are, in an already difficult context made more challenging by COVID19 and its political and economic impacts (and new health concerns and needs for physical distancing) are putting these connections at the forefront. Abolitionists, in particular, must work to ensure that their work develops in solidarity with the ongoing struggles for Indigenous sovereignty and return of land, struggles which were indeed shutting Canada down right as the COVID19 pandemic hit.